|

| Cover Painting by R B Farrell |

|

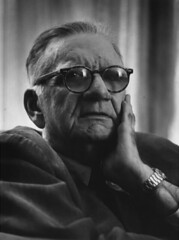

| Evan Hunter pictured 2001 a.k.a. Ed McBain a.k.a. Curt Cannon (1926 - 2005) |

When the

police find that Matt is involved, Lieutenant Miskler puts a tail on him, the

wonderfully named Albert de Ponce detective 3rd/Grade. Matt’s

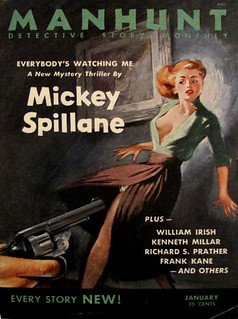

treatment of women here is rough even by the standards of the old Manhunt

magazine (where Matt Cordell first appeared). Extra-marital

relationships are rife in this book, and another murder is on the cards before

the end. But what really causes the trouble is that everyone – everyone – is lying. This is real noir, great noir, the pace is breathtaking and I was hooked from the start.

The first Cordell short story Die Hard written under the pseudonym ‘Curt Cannon’

appeared in the first issue of Manhunt magazine, January 1953. The Gutter and the Grave

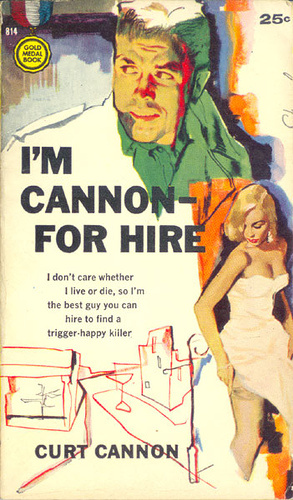

was originally published as I’m Cannon – For Hire under that pseudonym (the title was one that Evan Hunter hated, according to Booklist). Charles Ardai, editor of

Hard Case Crime writes of the character’s name “Cannon was a name foisted upon

McBain by the editor’s at Gold Medal; the character’s original name in his

magazine appearances was Matt Cordell. When McBain decided to let us reprint

the book, he asked us to change the character’s name back to what it had

originally been.”

Ardai’s – and Lawrence Block’s comments can be found here:

Vintage Sleaze Paperbacks

Ardai’s – and Lawrence Block’s comments can be found here:

Vintage Sleaze Paperbacks

Three episodes of Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer were based on Hunter’s stories (as Curt Cannon). Evan Hunter had just finished proofing the galleys of the Hard Case Crime reprint of The Gutter and the Grave when he died of laryngeal cancer